The owners of the textile mills kept the windows closed. This was not in consideration of the workers sweating away at the spinning machines, but in order to keep the cotton threads happy, the hot and humid atmosphere preventing them from breaking. The air was thick with lint and dust and with no airflow, many workers developed “brown lung” from years of breathing in cotton particles. The constant racket of machinery drowned out the happy chatter of children playing by the mill.

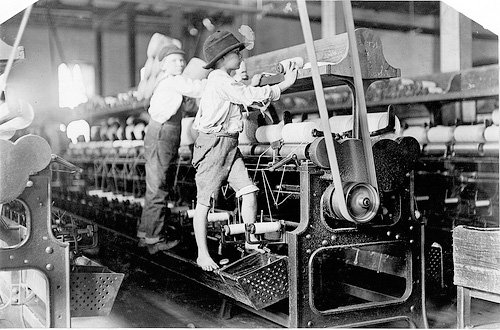

Suddenly, the machines would all stop and the “throstle jobber” would blow his whistle. This was the signal to the young doffers, some as young as seven, that it was time to “doff” or remove the bobbins full of spun fiber and replace them with empty ones. This was a task that required little strength but much dexterity; a job well suited to children and their small, nimble fingers. The doffers would rush into the factory barefooted and begin their hurried work, climbing up and down the spinning machines to doff the full spindles. Accidents were many and pay was little, but the doffers went about their work as quickly as possible so that they could get back to playing before the next whistle from the throstle jobber.

Young doffers | Lewis Hine

To many American children in the late 19th-early 20th centuries, this was their daily routine. No school, no reading or writing or arithmetic, just the daily schedule of playing within earshot of the factory interrupted by the hurried doffing of the spinning machines. The conditions were demanding and they were paid very little, but this was their reality and they did as they were told.

The general public in the early 1900s thought of child labor predominantly taking the form of children pitching in on farms and other family-run agricultural ventures. Many did not realize that in the process of industrialization, many children were beginning to become part of the manufacturing machinery, often putting in 12-hour days Monday-Saturday. According to the 1900 census, 1.7 million children (nearly 1 in 6) under the age of sixteen were employed in “gainful occupations” such as those in the factories. By 1910, this number had jumped to over 2 million, with the majority of these children never setting foot in school. Many could not even write their names. This was appalling by any measure.

A group was organized to bring about change in child labor in the United States and in 1904, the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) was officially formed. Two years later, they would hire a photographer who would forever change the course of child labor in the developed world.

Lewis Hine was born in 1874 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. His father ran a cafe while his mother was a school teacher. When Hine was only 16, his father died in a tragic accident and he was forced to become the financial provider for his family. He spent long hours at various poorly paid jobs but was laid off three years later when the economy took a downturn. He and many other adults in the factories of the day were replaced by children, who could be paid at a much lower wage. Hine managed to eke out a living at various odd jobs and this early work experience would come to inform his later work in photography.

By the time the NCLC met Lewis W. Hine in 1906, he had been honing his eye for photography and finding his subject matter. Hine first found his vision with immigrants at Ellis Island and later in the streets of New York and Philadelphia, documenting the children working as newsies, shoeshiners, or trash collectors. Hine’s calm demeanor and appropriate tone with children disarmed them as he gained access into their hidden world and documented their reality. His photographs from this time period are haunting and captivating, their minor subjects staring into the lens with tired, listless eyes.

Hine was employed full-time as a photographer by the NCLC in 1908 and for a full decade, he traveled across the United States with his 50 lb. camera equipment in tow documenting the state of child labor in the United States. He traveled nearly 50,000 miles/year by car and train, occasionally with his wife and young son in tow. The factory owners were not too keen on having their child laborers photographed and Hine’s commission was fraught with danger and threats of violence. To gain access, Hine posed variously as a photographer for a postcard company, a fire inspector, a bible salesman, or as a reporter.

Young cotton picker | Lewis Hine

Hine photographed children working in strawberry fields and cranberry bogs, on beet farms and tobacco plantations. He visited the canning factories on the Gulf Coast to document the children there shucking oysters and peeling shrimp. Hine visited the coal mines of Pennsylvania, where a particularly high number of deaths and accidents occured. And, on many occasions, Hine spent time in the textile millls of the South and Northeast, where the photographer first met the doffers.

Young shrimp picker | Lewis HIne

Young breaker boys | Lewis Hine

Hine’s images were published in many magazines and newspapers, helping to inform the general public of the terrible conditions under which these children were spending their young lives. With his campaign against child labor, Hine is regarded as one of the first examples of a photographer affecting social change. His photographs greatly aided in turning the tide against employing young children and beginning in the 1920s, many states began to regulate child labor for the first time. Finally, in 1933, the Federal Government outlawed child labor in mills once and for all.

Young greaser | Lewis Hine

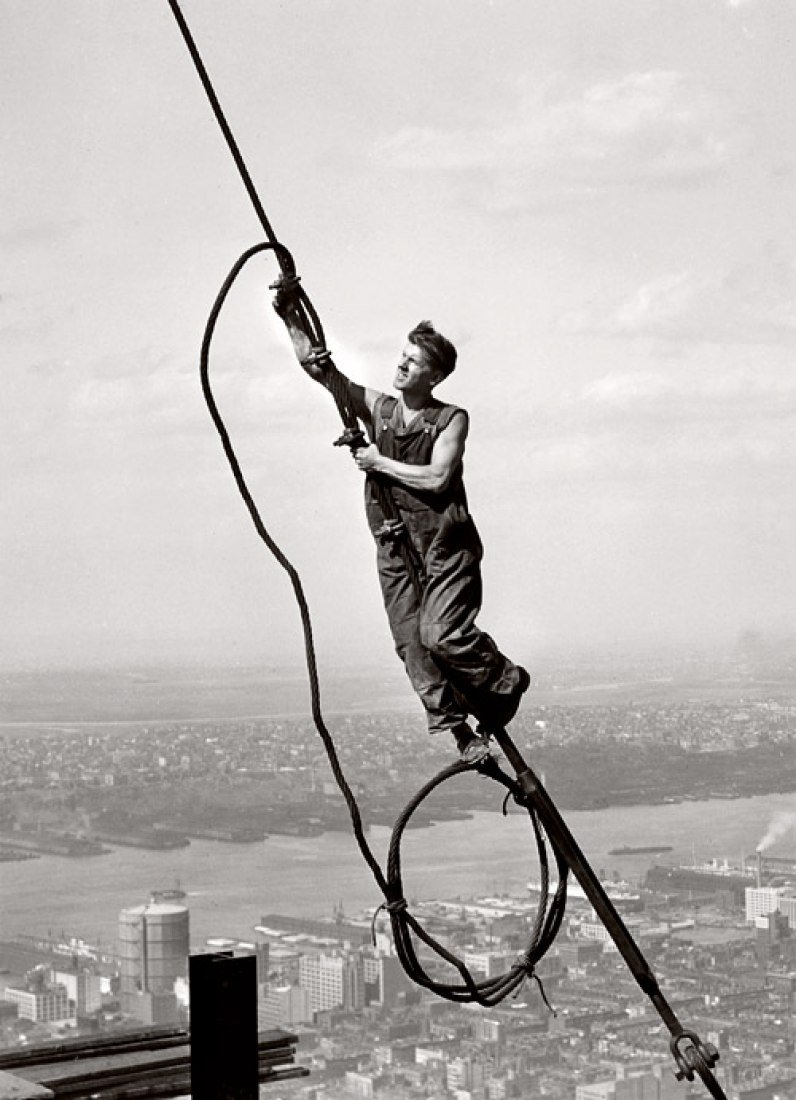

Lewis W. Hine continued to celebrate workers in his photos and sought to heighten the way they were represented in society. He went on to create a fantastic series of photographs of workers building the Empire State Building, lugging his 50 lb. camera equipment up long ladders and dangling in a basket 1000 ft. above the street to capture stunning images of the men atop metal girders. His commissions eventually declined as younger generations began to regard his style as old-fashioned and his financial troubles mounted. His family home was foreclosed, he was forced to go on welfare, and a year after his wife lost her long battle with illness, Hine died in 1940 at the age of 66. The Hines were survived by their only child, Corydon, who often helped his dad on commissions and who donated all of their prints and negatives to art organizations.

Man at work on Empire State Building | Lewis Hine

It would take more than three decades for Lewis W. Hine to get his due recognition but his legacy in photography is immeasurable. He continues to impact photographers the world over as well as one humble mixed media artist in Glenn, Michigan. Thank you, Mr. Hine, for the tireless and wondrous work you did. Your legacy lives on.

The Doffer | acrylic, watercolor paper, kraft paper on stained maple panel | AVAILABLE IN THE SHOP

Inspiration for The Doffer | Lewis Hine